Books

Book Review: The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination

- The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination

- Harvard University Press, 656 pp.

The Once and Future Artist

There was a time when the artistic reputation of Sir Edward Burne-Jones did not bear thinking about. For much of the 20th century, Burne-Jones’s paintings and his designs for stained glass windows all but disappeared from the standard accounts of the great art of the 1800’s.

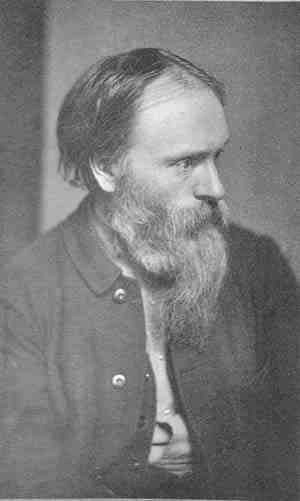

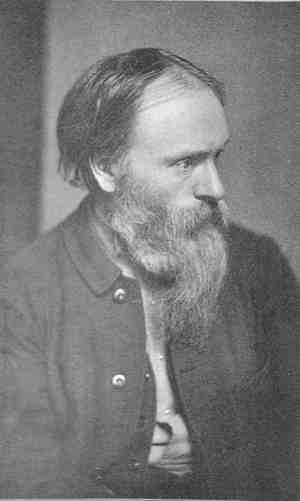

Edward Burne-Jones, c. 1882

Photograph by Frederick Hollyer

Impressionism was “in.” Burne-Jones’ evocations of Arthurian romance were decidedly “out.” Fiona MacCarthy provides a telling indicator of just how far Burne-Jones tumbled from the pedestal of fame and fortune. Toward the end of her new biography of Burne-Jones, MacCarthy quotes a sale price for one of his paintings, Love and the Pilgrim. In 1898, this painting sold for the then hefty sum of £5,775. In 1940, Love and the Pilgrim was purchased for £21.

You won’t get a Burne-Jones painting at auction for anywhere near £21 today. After decades of languishing in the shadows, Burne-Jones is back on center stage.

Fiona MacCarthy deserves a good bit of the credit for Burne-Jones’ reversal of fortune. In 1994, she published a massive and magisterial account of the life of William Morris, the life-long friend and colleague of Burne-Jones. MacCarthy’s book provided a much needed reassessment of how these two tireless champions of Britain’s traditional art and crafts achieved an amazing degree of success.

The Last Pre-Raphaelite is a worthy successor to MacCarthy’s life of Morris. It is able to treat the working relationship of Burne-Jones and Morris without the degree of attention to British politics that was necessary in the earlier book. Yet, the contrast between their approaches to art – and the occasional strains in their friendship – are well-documented here. Burne-Jones, the son of a picture frame maker, was knighted in 1894. Morris, born into an English gentry family, embraced Socialism and became a radical political theorist.

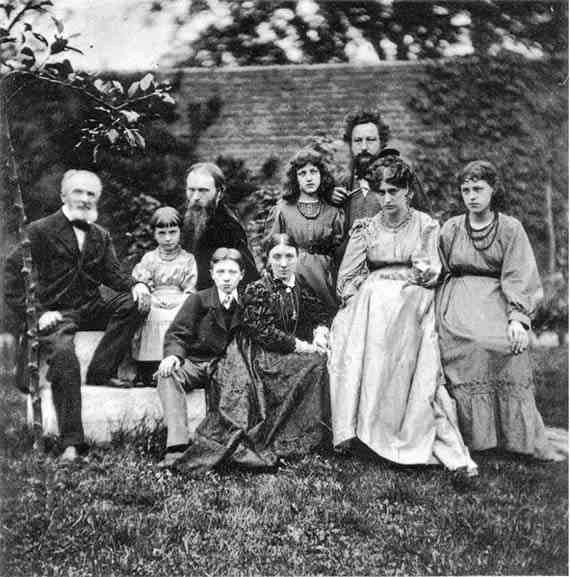

The families of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, 1874, photographed by Frederick Hollyer in the garden at The Grange, Burne-Jones’s home in Fulham. Left to right: Edward Jones (Burne-Jones’s father), Margaret Burne-Jones, Edward Burne-Jones, Philip Burne-Jones, Georgiana Burne-Jones, May Morris, William Morris, Jane Morris, and Jenny Morris.

Edward Jones, the hyphenated name came later, was born in Birmingham in 1833. Birmingham was one of the powerhouse cities of the Industrial Revolution. It was a dynamic place in economic terms, but a grim and unhealthy site for a boyhood home. Burne-Jones was a survivor, described by a nephew as having “iron and granite” in his soul. However, when the opportunity to go to Oxford University availed itself, Burne-Jones did not look back.

For all of his toughness and resilience, Burne-Jones was also an incurable Romantic. His philosophy of life and art can be summed up in a famous quote:

I mean by a picture a beautiful romantic dream, of something that never was, never will be – in a light better than any ever shone – in a land no-one can define or remember, only desire – and the forms divinely beautiful.

It was at Oxford University that Burne-Jones found divine beauty and William Morris. They shared a love for medieval themes, what we now call Gothic Revival, and were attracted to the art of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Founded in 1848, the Pre-Raphaelites were a loose confederation of young artists in revolt against the false veneer of academic art. John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt were towering individualists with ideals and egos to match.

In 1856, Burne-Jones and Morris assisted Rossetti with painting a series of murals with Arthurian motifs at the recently constructed Oxford Union Society debating hall. The murals began to disintegrate almost as soon as they were completed because the plaster walls had not been correctly primed.

In many ways, the Oxford Union Society experience prefigured the linked careers of Burne-Jones and Morris. Their “reach” often eluded their “grasp.” Burne-Jones drew a witty caricature of himself surrounded by unfinished canvases. Morris, in his mania for authentic medieval regalia, once donned a replica of a 14th century knight’s helmet and was unable to get it off his head until frantic efforts liberated him. Burne-Jones called his friend “Topsy.”

Pratfalls and over-booked work orders aside, Burne-Jones and Morris made for a good team. Each had an industrial-strength work ethic and their comparative strengths complemented the other to perfection. Burne-Jones had an uncanny ability to place his long-limbed, angelic figures in artful poses, whether on canvas or in his cartoons for stained glass or tapestries, and possessed a superb color sense. Morris, whose private fortune funded the company which crafted products based on their designs, was a great “hands-on” man. He combined boundless energy with the ability to integrate traditional techniques from folk art into the work flow of the “Firm.”

Burne-Jones and Morris also shared in the Pre-Raphaelite rapture over beautiful, goddess-like, young women. “Stunners” was their accepted term. It was a passion, normal in undergraduates, which would cost them dear as they continued it into their mature years.

At first, all went well for Burne-Jones, as he had the good sense to marry Georgiana Macdonald, “Georgie,” the daughter of a Methodist minister. Short in stature, but great in soul, Georgie was intelligent, virtuous and believed in Burne-Jones’ art. Then, in 1866, Burne-Jones engaged a young woman of Greek descent, Maria Zambaco, as a model for a mythology-themed work, Cupid Delivering Psyche.

Burne-Jones strayed from the straight and narrow path. He fell – and fell hard.

Thanks to Georgie’s saintly forbearance, their marriage and Burne-Jones’ reputation was saved. The affair with Maria Zambaco eventually flamed-out. But Burne-Jones never entirely recovered from this fall from grace.

For the rest of his life, Burne-Jones remained infatuated with an ideal of ethereal, unsullied, virginal womanhood. Young womanhood, to be exact. He found models for this ideal close to hand. These included his own daughter, Margaret, Frances Graham, the daughter of William Graham, a prominent member of Parliament and his major patron, and Mary Gladstone, daughter of the Prime Minister, William Gladstone.

Given the social standing of these young women and Burne-Jones’s sense of honor – dented, but still functioning – he almost certainly never went beyond the level of platonic love for them. But it was unhealthy all the same, for Burne-Jones wished desperately for them to remain in a suspended state as perpetual muses. When they married, he reacted with sullen, barely concealed disappointment.

MacCarthy writes with empathy, if not approval, of Burne-Jones in this respect, describing him as “a creature less of sexual treachery than of peculiar elasticity.”

Given this anomalous state of mind, Burne-Jones could remain devoted to the ever-faithful Georgie, while still engaged in an updated, very Victorian, version of medieval courtly romance. It is no accident that it was Maria Zambaco who modeled as the mythological statue who comes to life in Burne-Jones’s cycle of paintings, Pygmalion and the Image. In this case, art mirrored life. The rest of his dream passions played out on the surface of his paintings. These were works, as MacCarthy aptly describes them, of “magnificent strangeness.”

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), The Heart Desires, Pygmalion (II of IV), Second Series, 1875-78

Oil on canvas

Birmingham City Museums & Art Gallery, Birmingham, England

MacCarthy’s biography of Burne-Jones succeeds on all levels. It is compellingly readable, blending prodigious research into a lively, thoughtful narrative. If Burne-Jones still remains something of an enigma, MacCarthy has pressed closer to the mystery of this strange, beauty-obsessed man, than any previous author. She has found a key to what Burne-Jones himself described as “the innermost soul that can always be kept locked.”

Ed Voves is a freelance writer, based in Philadelphia, where he lives with his wife, the artist Anne Lloyd, and a swarm of cats who love curling up with good books.

Mr. Voves graduated with a B.A. in History from LaSalle University in 1976 and a Masters in Information Science from Drexel University in 1989. After teaching for several years with the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, he worked in the news research department for “The Philadelphia Inquirer” and the “Philadelphia Daily News,” 1985 to 2003. It was with the “Daily News,” that he began his freelance writing, doing book reviews and author interviews with such notable figures as Umberto Eco, Maurice Sendak, and Peter O’Toole. For the “Inquirer,” he specialized in reviews of major historical works. Following his time with the newspapers, he worked as an independent researcher for Knowledge@Wharton, the online journal of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He joined the staff of the Free Library of Philadelphia in 2005 and is currently the branch manager of the Kingsessing Branch in southwest Philadelphia. In 2006, he began writing for the “California Literary Review.” History of Yoga

You must be logged in to post a comment Login